4 Ways Zelle Let Fraud Flourish (and Why New York Is Now Suing)

Zelle markets itself as “fast, safe, and easy.” Fast? Yes. Safe? Not exactly. New York Attorney General Letitia James just sued Zelle’s operator, Early Warning Services (EWS), for turning a peer-to-peer payment shortcut into a fraud-free-for-all. If that sounds familiar, it’s because the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) filed almost the same case, and then, after a leadership shake-up, quietly dropped it. Below are the four design choices at the heart of both complaints.

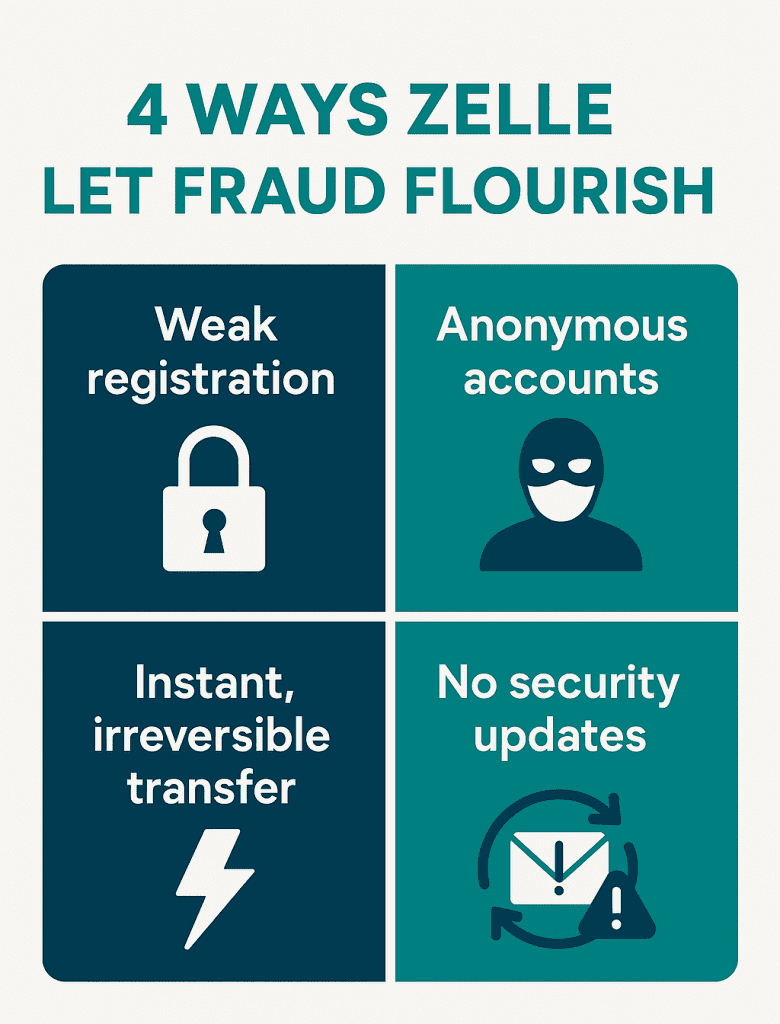

1. Blink-and-You’re-In Registration (No Real Identity Check)

It’s 2016, and payment apps are booming. Venmo moved $1 billion, and PayPal was moving truckloads of cash too. That is when EWS launched Zelle. New York says EWS “hurried Zelle to market” and let anyone sign up with little more than an email or mobile number. Zelle’s registration process allowed fraudsters to create multiple Zelle accounts (sometimes up to 20 different accounts using a single email address). This is like a bank letting you set up one checking account linked to 20 different P.O. Boxes. Outrageous. With all these accounts in hand, scammers would be able to flip them between bank accounts and switch banks before any bank caught on. But even if the bank flagged any one account as suspicious, Zelle let the scammer have another 19 that they could use to continue stealing money.

The CFPB complaint backs that up: Bank of America, Chase, and Wells Fargo all “implemented only limited authentication, verification, and registration requirements which permitted bad actors onto the Zelle network.”

Takeaway: A front door with more holes than Swiss cheese guaranteed scammers easy entry.

2. Mystery Recipient Screens (Limited Information for Senders)

Both regulators slam Zelle for showing senders almost nothing about who’s on the other end. The NYAG cites “limited information displayed to consumers” that let crooks pose as “ConEd Billing.”

The CFPB’s complaint reveals more details, as it alleged Zelle allowed scammers to create accounts that “falsely indicated the user was a large business or government entity,” even though Zelle doesn’t allow either to use its platform. (Now, if you walked over to your local Bank of America and told them you wanted to open an account under the name “Internal Revenue Service Payment,” how long do you think you have before they call the cops? Apparently, the rules on Zelle were different.) Zelle even allowed emails that impersonate Zelle itself and the banks that own Zelle.

The CFPB notes EWS knew this gap “increases the risk of fraud and makes it more difficult for consumers to avoid transferring funds to bad actors.”

Takeaway: When you wire money to a black-box recipient, it’s the perfect scam setup.

3. Instant, Irreversible Transfers (No Pause Button)

Zelle’s bragging rights—money available in seconds—also lock victims out of any claw-back window. New York labels this a “significant and foreseeable cost” of EWS’s design. Zelle’s emphasis on making funds available immediately after the transfer allowed for “quick getaways,” while eliminating any chance that scam victims would have to recover stolen funds.

CFPB lawyers went further by alleging that EWS “failed to stop transfers with unusual or suspicious characteristics that were likely to lead to consumer losses.”

Takeaway: Speed often beats security, and scammers know it.

4. No Security Updates (Until The Government Forced Its Hand)

By 2019, Zelle was rife with fraud. According to New York, millions of people lost hundreds of millions of dollars from scams on Zelle. While the number of fraud victims soared, EWS and the banks earned millions of dollars.

Some employees at EWS thought the company should make changes to its security to keep fraudsters off the platform. These changes came in July 2019, and New York calls them a “suite of modest, yet critical, security enhancements.” Still, when it came time to implement it, Zelle shrugged. New York states that they not only failed to implement these limited security enhancements, but also did not meaningfully enforce the existing rules that were in place to detect, prevent, and address fraud.

Only after people lost more than one billion dollars and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau launched a significant investigation, along with several members of Congress, did EWS finally adopt the basic security improvements it had proposed four years earlier, according to New York.

Takeaway: Bad actors were free to hop from account to account, recycle emails, and continue scamming.

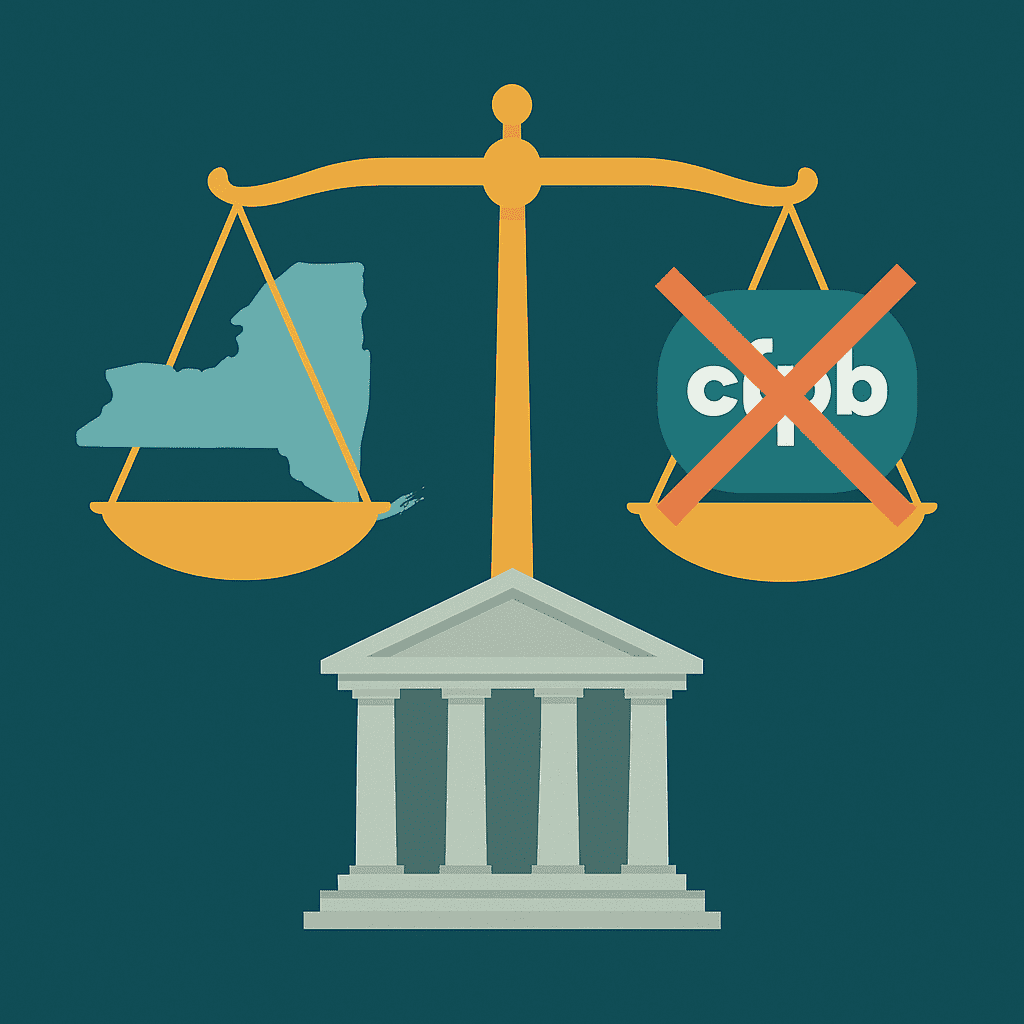

Why Are There Two Cases? And Why Did Only One Survive?

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau filed its lawsuit on December 20, 2024. The Bureau alleged ten counts against EWS and three banks: Bank of America, Chase, and Wells Fargo. The complaint was substantial. It spanned nearly one hundred pages and laid out strong evidence against the defendants. The Director of the Bureau said this when the lawsuit was filed:

In case after case, banks routinely denied requests for help, turning a blind eye even when customers provided clear evidence that criminals had taken over their accounts and that the transactions were unauthorized — including police reports documenting the crimes. The banks dismissed these claims based on faulty logic, for instance claiming that because a stolen phone had been used for legitimate transfers in the past, all future transfers must also be legitimate. Instead of providing legally required assistance, banks often abandoned these victims, sometimes even telling them to contact the criminals themselves and request their money back.

Three months later, the agency (under new leadership that thinks protecting people from scams is an example of a “woke and weaponized agency”) dropped the Zelle lawsuit. The agency dismissed the case “with prejudice,” which means it cannot be revived in the future.

Five months later, New York brought its own case against EWS. When it was filed, the Attorney General said, ““No one should be left to fend for themselves after falling victim to a scam.”

What Happens Next?

The case is pending in New York’s trial court (confusingly named the Supreme Court of New York). New York is asking a court to force Zelle to adopt “basic network safeguards and any other antifraud measures that are necessary to protect consumers and limit consumer harm from fraudulent activity.” The state is also asking for Zelle to have to refund all fraud victims who live in New York.

Many folks, including myself, believe EWS will try to get this case thrown out quickly. Either way, it’s a long road, and as important as this case is, it is only one state. We have a lot of work ahead of us. We need all hands on deck, from the state regulator to the individual people who are victimized. We all need to push back and demand better.

About the Author

Angel E. Reyes is a former federal enforcement attorney at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Trade Commission. After bringing enforcement actions against the largest U.S. companies, which resulted in over $100 million returned to consumers, he left the government to open Power to the People Law PLLC. This law firm focuses on protecting people’s homes and bank accounts.

Disclaimer

Informational only. Attorney advertising. Not legal advice.